Inspiring people today by recovering erased history

PortSide NewYork's African American Maritime Heritage (#AfAmMH) program was launched May 2018. PortSide started this program because these are relevant WaterStories all Americans should know. We launched this, before properly “ready” and funded, because of the virulent racism, fake news and fake history about USA race history that was and is resurgent.

AfAmMH encompasses stories of Black achievement, struggles against the sea, struggles against racism, and aspects of daily life and work (it’s not all derring-do) around the country. The maritime part of the African American story is largely forgotten, even though some of these stories and people were famous in their day. As we mention in the ABOUT section below, historians of the Underground Railroad are just recently, since the launch of this page, recognizing that they had largely missed the role of maritime (boats, waterways, maritime workers) in that oft-told story. Thus, this AfAmMH program reflects how this history was erased and efforts to erase it in the present. You can find our posts about this program on social media via #AfAmMH.

-

When PortSide prepared to launch AfAMMH, we expected to find many stories about how maritime figured in the Underground Railroad; because as maritime people, we knew that the waterways were how ideas and people moved most readily and longer distances during the period of the Underground Railroad. We did not find a lot, but we learned in 2023 that our instincts were right.

In 2022, new scholarship emerged, and a conference was held that addressed the fact that the study of the Underground Railroad had been overly land-focused and had missed that the waterways were a MAJOR escape route. More on that in one of our sections below.

Also clear to us over our five years of work on this is that mainstream American history had erased the prevalance, during the age of slavery, of Black efforts at physical rebellion from group slave revolts to individual acts of self-defense using violence. One such story is William Tillman’s below. Back in the age of slavery, slave owners suppressed such news to prevent it sparking more attempts at self-liberation, and history (dominated by white people) carried that silence forward.

Also clear is that historians have overplayed the role of whites in the Underground Railroad and abolition and minimized or erased the powerful roles and number of Black actors.

As of early 2023, the most visible national example of attempted erasure comes from Florida’s Governor Ron DeSantis who claimed that the pilot AP class in African American history is “inexplicably contrary to Florida law and significantly lacks educational value.” DeSantis uses the strategy of cherry picking which parts of Black History are valid and deeming some flawed for being “woke.” In his framework, queer history, intersectionality, critical race theory (CRT), Black Lives Matter, “systemic inequality” or “systemic” anything relating to race is an issue, as are campaigns for restitution and more.

New Jersey’s Governor Phil Murphy pushed back and is expanding use of the AP course from one to twenty-six New Jersey schools. More about that and the curriculum content here.

After several weeks of uproar, the College Board announced their regrets for not having called out earlier what they deemed “slander” by DeSantis, also saying “we were naive not to announce Florida’s rejection of the course” and we were not “in frequent dialogue with Florida about the content” as claimed, and that Florida had misrepresented their work with a politicking strategy.

Noted scholar and a contributor to the AP curriculum, Henry Louis Gates weighed in via a New York Times op-ed covering the long history of whites using erasure and disinformation to attempt thought control, both to subjugate Blacks and to convince whites of their superiority.

All this is a lesson in the struggle to research and tell Black History up to today, showing how Black history remains a subject that some white people will vigorously try to erase — from the moment the history is made, to the telling of it going forward, and also retroactively.Moving on to what we offer here: These resources are not intended to be comprehensive; they reflect the limitations of our own capacity to do deep, original research. These topics are an introduction and starting point as we research and learn ourselves. We seek partners to grow AfAmMH. Please get in touch if you want to get involved or have suggestions for us. You can help by donating to our AfAmMH library, which we make available to the public. We accept used books in good condition as well as new ones. Our growing list of books is at the bottom.

African American Red Hook WaterStories - Brooklyn

-

"The American Revolution created opportunities for some enslaved Blacks to obtain freedom. Self-interested economic and military reasons prompted the British to declare the freedom of all enslaved Blacks in America who joined them in New York harbor as Royal Navy seamen, British privateersmen or as laborers in the British Army - thus providing Blacks with financial independence. But, in a foreshadowing of 20th century racial conflicts on New York’s waterfront, Black maritime workers found themselves largely shut out of dockyard work due to white artisans’ resistance. At the same time Black mariners serving on captured British ships often found themselves sold into slavery. When the war ended, the best option for most of the British-freed Blacks was to flee away from the United States but for the vast majority of enslaved Blacks a door to freedom was firmly shut."

-

Four years before the American Civil War, a legal battle emerged from a situation that occurred aboard a steamship from Savannah to New York. One of the passengers, Thomas Steele, a light skinned man, was accused of being a fugitive slave by another passenger. There was no proof whatsoever to support this. Nevertheless, as described in the The New York Herald, December 4, 1857, upon the ship’s arrival in New York, Steele was brought to the home of a Thomas McNulty, a grocer and boarding house keeper in Red Hook, where he was to be held until he could be sent back to Savannah.

However, before this could occur, a petition was made to City Judge, E. D. Culver. It informed the court of Steele's plight, explaining that he was being “detained and restrained of his personal liberty.”

The judge ordered that Steele be removed from McNulty's house and brought before him. McNulty was also ordered to appear before the judge, but he refused. With no one giving evidence against Steele, Judge Culver released him – allowing him to disappear – and charged his captors with kidnapping. Local papers in reporting the story, varied greatly in their sympathy to Thomas Steele.

-

“The race question is extending itself upon the seas." At the beginning of the 19th Century, one out of five American sailors were Black; at the start of the 20th Century, Black sailors in Brooklyn were facing severe job discrimination.

-

In the summer of 1850, an African-American woman was abducted and brought to Red Hook Point - just below the Atlantic Dock - to be put on a schooner and brought to a Southern slave state. The captors told suspicious workers in the area that the woman was a runaway slave – this the woman vehemently denied. Two of the workmen ran to get the police, and when they returned the slavers were gone leaving the woman free.

-

A pivotal event in the ending of slavery occurred on December 5, 1860, in Atlantic Basin, Red Hook when the slave ship ERIE was sold at government auction after being captured off the coast of Africa for being engaged in the illegal act of slaving (shipping captured Africans to have them sold into slavery). The ERIE’s captain and owner, Nathaniel Gordon, was then executed for engaging in the slave trade. President Abraham Lincoln himself made sure that an example was made of Captain Gordon and his ship ERIE.

LINK: https://redhookwaterstories.org/exhibits/show/slaveship/full-article--slave-ship

Communities & Themes

-

The US Coast Guard’s historian’s office compiled a chronology of notable African Americans in their service. Starting in 1795, the list, largely of notable firsts, runs through 2019. Also available on the site is an extensive historical bibliography of Minorities and the U.S. Coast Guard and an account by Commander Carlton Skinner of the USS Sea Cloud, IX 99, which became an experiment in racial integration aboard U. S. naval vessels from December 1943 to November 1944.

-

"By the 1860s, the Chesapeake Bay became the primary source of oysters in the U.S. This created an industry in need of strong labor. The availability of jobs and relatively low start-up costs for new watermen lured many newly freed Blacks to the region. In addition to harvesting the Bay's bounty, many also found jobs building boats and processing the day's catches."

"New African-American communities sprung up along the Bay's shores. These communities became economic and cultural centers for Blacks in the region. During the early 1900s, it was not uncommon to hear men singing while hauling in seines full of fish. These rhythmic songs, known as chanteys, are rooted in African tradition. Chanteys helped the men coordinate their movements and control the pace of the grueling work. Many watermen believed that singing chanteys helped them haul in nets faster and more efficiently than those who did not sing." [Description from chesapeakebay.net page: African Americans in the Chesapeake]. The Chesapeake Bay website also discusses: Six ways African-American history helped shape the Chesapeake.

In the same current, The Chesapeake Bay Foundation website provides short bios of some “Black Heroes of the Bay” (2018).

Focusing on this topic is also the Blacks of the Chesapeake Foundation. They work “to bring to light the maritime history of African Americans in the Chesapeake Bay”. They maintain a collection of records, artifacts, genealogies, and more than 40,000 photographs representing 200 years of African American life and work in the seafood and maritime industries. Links on their website include: A vanishing legacy: Black Captains of the Chesapeake Bay, African-American Land Conservation & Preservation (complete with sign language interpretation) and other articles relating to Blacks of the Chesapeake Bay.

NOAA’s National Marine Sanctuaries interviewed the founder and past-president of Blacks of the Chesapeake Foundation: “Vince Leggett Tells of African American Ties to History, Culture, and Waterways of Chesapeake Bay Region”

-

The Sandy Ground community is the oldest continuously inhabited free Black settlement in the United States. It began with ferry boat operator Captain John Jackson. In 1828 he was the first Black person to own property on Staten Island, buying in what is now the South Shore community of Rossville. He was joined by freed black men and women who took up oystering and farming.

Over time, more Black oyster fishermen joined them from Maryland, Delaware and elsewhere in New York, finding in Sandy Ground a welcoming place to practice their trade as free people and thrive. Ten families living there today trace their roots back to the original settlers.

“Oysters can still be found on the Conference House beaches" according to the Sandy Ground Historical Museum website.

In December 2019, Mayor de Blasio announced that one of the new Staten Island ferries would be named “Sandy Ground.” The ferry started service in early 2022.

Sandy Ground in Wikipedia

Sandy Ground Historical Society listing in NYC-Arts

Sandy Ground in Forgotten New York

"They Will Not Be Moved; A Bastion of Black History Amid S.I. Development" The New York Times, November 4, 2003

“Staten Island Ferry Facts,” https://www.nyc.gov/html/dot/html/ferrybus/ferry-facts.shtmlNYC DOT

-

Information on this is in several of the books below and is covered in a book dedicated to this topic “Whaling Captains of Color – America’s First Meritocracy” written by Skip Finley.

Here are links to two of Skip Finley’s articles on the topic:

• For Whaling Captains, Diversity Flourished

• Black Whaling Captains Found Liberty at Sea

And two audio/video links of Skip being interviewed:

• Skip Finley on Whaling Captains of Color: America's First Meritocracy, Nantucket Book Festival, August 2020

• The History of Whalers of Color, All of It, WNYC.org

-

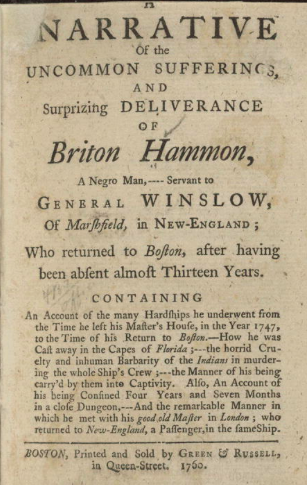

In 1839, captured Africans aboard the schooner AMISTAD bound for slavery in America took control of the ship and tried to sail to freedom. The ship was apprehended off the coast of Connecticut. Their case reached the US Supreme Court and was notable in the abolition movement. There are two stories related to the ship AMISTAD where Women’s History and African American Maritime Heritage intersect.

One of the four captured children on the AMISTAD headed towards slavery was Margru (sometimes spelled Margu) from Bendembu, Mandingo country about 100 miles from what is now Freetown, Sierra Leone. After the AMSTAD court case was resolved in favor of the Africans, she returned to Africa but later came back to the USA to go to Oberlin college, which had, as of 1835, "an official policy admitting African American students, both male and female—the first college in the country to do so,” from an Oberlin link with alot of Margru's story. We learned about Margru thanks to the ever-informative content on the Facebook page of Parting Ways Cemetery and the Hartford Courant article that they shared explaining that Margu’s story is brought to life by historical actor Tammy Denease.

As we looked into Margru’s story we found a Wikipedia page that said that the file used by the captured Africans aboard the AMISTAD to break their shackles was brought aboard and hidden by a woman. If so, a woman had the tool that was used to physically liberate all the shackled Africans on the AMISTAD, an UNNAMED woman. We must point out that this is SO TYPICAL of what happens to women’s contributions: OVERLOOKED, UNNAMED, ERASED. Does someone know the name of this woman or want to take on this research project?

“On July 2, 1839, one of the Africans, Cinqué, freed himself and the other captives using a file that had been found and kept by a woman who, like them, had been on the Tecora” from https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/United_States_v._The_Amistad

-

The Black Surfing Association (EC) - Rockaways

The East Coast chapter of the Black Surfing Association was founded by Louis Harris in 2016. Harris, an African American, started surfing in 2006 after moving to the Rockaways. There he met Brian James, then the only other Black man in the water. Inspired by a love of surfing and the need to keep the local children active and occupied Mr. Harris now offers free surf lessons to any children who show up. About 35% of the Rockaway residents identify themselves as Black and nearly 30% as Hispanic.

• Black Surfing Association (EC) website. Also on Instagram

• Black Surfing Association (founded in California, 1975)

• Brian James, The Nautical Negro, Adventures of a Black Waterman, An Autobiography of an African American surfer. (website for book)

• Cheddar, “Black Surfing Association Combats Racism By Teaching Kids to Hang Ten,” by Michelle Castillo, September 14, 2020

• Surfer, “NYC Surfers Will Paddle Out For Racial Justice This Saturday,” by Owen James Burke, August 20, 2020

• The New York Times, “Surfing Remade in the Rockaways” Dec. 22, 2018

-

Steamship Historical Society of America’s lesson plan provides a nice overview of the history of black sailors in America.

-

Marcus Garvey’s Black Star Line was the first black owned and operated steamship company. The short-lived line (1919−1922), was envisioned by Garvey to create economic opportunities and pride among the Black Community by being completely owned, operated, and financed by black people, but a host of problems ranging from inexperience, overpaying for used boats in bad condition, and investigations by J. Edgar Hoover’s FBI ended the line.

Sources:

“The Black Star Line,” lesson plan of the Steamship Historical Society of America.

“The History Behind Chance the Rapper’s Black Star Line Festival,” by Ella Feldman, Smithsonianmag.com, December 22, 2022

“Black Star Line,” Wikipedia

“Marcus Garvey’s Black Star Line,” by Jay E. Moore, Ph.D, The Mariner’s Museum and Park, February 26, 2021

-

From 1840, the Colored Sailors' Home, located near the water in lower Manhattan, offered a place where Black sailors could stay between ships and jobs. There were similar places for other sailors, but Black seamen were generally not welcome there. The Colored Sailor's Home was also a center of activism. It was established by William Powell, Sr., a Black man. Albro Lyons, Sr. worked with him for a time and then established a similar place nearby. A report in 1848, in The Sailor's Magazine, and Naval Journal noted that home catered to the needs of the "2,200 colored seamen who sail out of New York." Quoting from the Carla Peterson piece below “On the Lower East Side, two colored sailors homes, one run by William Powell on Dover Street, the other by Albro Lyons on Vandewater Street, lay in close proximity. These were boarding houses for Black sailors, but also centers of Black activism; Powell’s housed a labor union for Black seamen while Lyons’s was a stop on the Underground Railroad. To complicate matters, they were also family homes.”

The Colored Sailors' Home was one of the many Black establishments that were attacked by violent mobs during the Draft Riots of 1863.

• The Sailor's Magazine, and Naval Journal. American Seamen's Friend Society, 1846

• Carla Peterson, Black Elites and the Draft Riots, New York Times blog, 2013

• 15 Underground Railroad stops in New York City, www.mswnyc.com blog, 2018

• Double ambrotype portrait of Albro Lyons, Sr. and Mary Joseph Lyons, Black Gotham Archive (accessed 2018)

• "Albro Lyons, Sr."1860. Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture, Photographs and Prints Division, The New York Public Library. The New York Public Library Digital Collections.

-

Maritime activity moves people and food and changes what and how people cook.

Rice in the Americas has a racial history, and maritime activity is part of the story. More broadly, slavery had huge maritime elements: shipping captured people; shipping food stuffs as part of the trade; naval battles with alliances along race lines. White northern Europeans had no experience growing or cooking rice; Africans did and were deliberately captured and enslaved to grow rice here. African American enslaved cooks were given European recipes and then gave them an African twist. Free Blacks continued this culinary tradition. Then, there is a variety of rice that reveals to historians, biologists, and geneticists stories of the African diaspora. One part of this story is the Merikins of Trinidad & Togago below. For more on the rice topic, see our 2019 blogpost.

• "Finding a Lost Strain of Rice, and Clues to Slave Cooking: The search for the missing grain led to Trinidad and Thomas Jefferson, and now excitement among African-American chefs," Kim Severson, The New York Times, Feb. 13 2018. https://www.nytimes.com/2018/02/13/dining/hill-rice-slave-history.html

• Michael Twitty, culinary historian and the author of ”The Cooking Gene: A Journey Through African American Culinary History in the Old South.” His webpage https://thecookinggene.com

Youtube videos: https://www.youtube.com/results?search_query=Michael+Twitty

Joe Frogger Cookies

Joseph Brown (1750-1834) and his wife Lucretia Thomas Brown (1772-1857) are known for creating a cookie favored by Massachusetts mariners and others: the Joe Frogger. The large cookie, originally made with sea water, rum and spices, has a long shelf life, suitable for sea voyages. Born into slavery, Joseph Brown’s mother was Black and his father a member of the Wampanoag Tribe of Gay Head on Martha’s Vineyard. Brown may have been freed for his Revolutionary War service. Both of Lucretia Thomas Brown’s parents had been enslaved. Joe and Lucretia ran a beloved tavern in Marblehead, Massachusetts. The building, known as “Black Joe’s Tavern,” still stands.

• “Joe Froggers: The Weight of the Past in a Cookie,” by Julia Blakely. Unbound, Smithsonian Libraries and Archives, November 1, 2016.

• “Encore for Lost Recipes,” by Clementine Paddleford. Evening Star. (Washington, D.C.), September 24, 1961, (includes a recipe)

• “Joseph & Lucretia Brown,” by Lauren McCormack, Marblehead Museum. 2021

• “Black Heritage in Marblehead: Joseph & Lucretia Brown,” by the Marblehead Racial Justice Team, YouTube

• “Joe Froggers: The legend of these rum-and-molasses cookies leads to a New England tavern owned by a Black Revolutionary War veteran,” by Leigh ChavezBush. Atlas Obscura

-

During the War of 1812 between the British and the US, the British offered freedom and a home in the empire for Black people in America who joined their side. Many became Marines, and men from Chesapeake Bay, and the coasts of Virginia, Maryland and Georgia formed six military companies. After the war they, their families, and their rice relocated to Trinidad & Tobago, where their community, known as Merikins, lives on. For more on this topic, see our 2019 blogpost.

• "The Merikins. America, Trinidad and Canada's forgotten history official documentary," Nu Generation Studios, YouTube video (accessed 2/10/2020)

45 min.

• "Merikins Celebrate 200th Anniversary in Trinidad - April 28, 2016," Hollis Clifton, YouTube video (accessed 2/10/2020). 2hrs 8 min.

• Who are the Merikens? - Travel Thru History - Quick History," Travelthruhistory, YouTube video (accessed 2/10/2020). 1 min.

• THE MERIKINS: FREE BLACK SETTLERS 1815-1816, National Library of Trinidad and Tobago. (accessed 2/10/2020).

• Jill Neimark, "A Lost Rice Variety — And The Story Of The Freed 'Merikins' Who Kept It Alive," The Salt, National Public Radio, May 10, 2017. (accessed 2/10/2020).

• PBS, “Black Sailors and Soldiers in the War of 1812,” The War of 1812. Text and video. (accessed 2/10/2020).

-

Destinations in North America were only a small part of the Atlantic slave trade. Slate magazine created an interactive map covering “315 years. 20,528 voyages. Millions of lives” which provides a visual representation of known ships leaving Africa with enslaved people.

There is a deep and growing archive about slave ship voyages, representing decades of research, on the website Slave Voyages. An example of the data that can be found on the site is a list of known ships traveling to New York, from other North American ports (largely the Caribbean) and how many captives they held. To learn more about how that archive came to be, find other related links, and learn about the moral aspects of handling this data, see this excellent essay in the New York Times by Jamelle Bouie. He was one of the creators of the Slate map above.

-

Although the American Civil War lead to the abolishment of slavery in the United State, the North by no means was innocent when it came to slavery. The Atlantic Black Box Project is a working to bring attention and scholarship to New England merchant ships role in the slave trade. New York Ships are included too. A book below “Complicity, How the North Promoted, Prolonged and Profited from slavery” delves into how many aspects of the maritime industry in the North revolved around slavery. The Last Slave Ships: New York and the End of the Middle Passage is the title of John Harris’s 2020 book detailing how long after the transatlantic slave trade was officially outlawed, slave traders made NYC a key hub in their operation in the 1850s and 60s and how the US Government before shutting it down in 1867 ignored or even abetted this human trafficking. Link: https://yalebooks.yale.edu/book/9780300247336/last-slave-ships

-

H.E. Ross researches northern Caribbean maritime heritage. He maintains a Facebook page about Cayman maritime heritage among other endeavors. He culled a list of African and African descent sail designs on this blogpost. He credits the source as the book Aak to Zumbra - A Dictionary of the World's Watercraft. We would welcome more info from experts on this area.

-

The history of Black Americans and swimming is fraught because racism excluded Blacks from beaches and pools, meaning that over time, few Blacks learned to swim. According to an International Swimming Hall of Fame (ISHOF) document “African American Swimming History” 1866 to 1945 was the “for Whites Only” period of swimming in the USA. The legacy of Jim Crow swimming rules is long. According to the CDC, Black children at the national level drown at much higher rates in pools than whites. In NYC, Blacks drown at city beaches at a higher rate than whites. Fear of water and swimming is a result of this history for some Black American ADOS (American Descendants of Slavery) whereas Black Americans from the West Indies come from island, beach and boat cultures. Thus, for some Black Americans, learning to swim means facing inter-generational trauma. In that spirit, here is a personal testimonial about a Black mother teaching her son to swim, and see the group Black People Will Swim. According to the International Swimming Hall of Fame (ISHOF), the recent history of Black swimming in the USA inverts what had been the state of affairs for a millennium: Africans were adept swimmers when swimming had fallen out of favor with Europeans after early Christians closed the Roman baths in the 5th century, scandalized by what happened there. This all relates to Blacks in maritime because a fear of water or swimming can be a deterrent for getting involved with boats.

-

Recently resurgent is awareness of William Still, the African-American abolitionist and his 1872 book “Underground Railroad” which recounts stories of escape, a significant number of which involve fleeing on East Coast Ships. Still’s book popularized the phrase “Underground Railroad.”

The telling of the history of the escape routes of enslaved Blacks in America, known as the Underground Railroad, has largely focused on land routes. New scholarly research and a new appreciation of old writings are beginning to tell a more complete story by recognizing the major significance of ships and waterways in the journeys of people to freedom.

“The absolute fundamental bedrock reason for why escape by water worked and the conditions existed to get people out of places very, very far away from the free states was the labor force on the waterfront of the entire Southern Seaboard, every little inlet and port city and tidal waterway and river … down to the ports for loading onto larger ocean going vessels to take them to market. All of that labor was enslaved African American labor,” says Timothy Walker, PhD. Walker is the editor and contributor to the 2021 book Sailing to Freedom: Maritime Dimensions of the Underground Railroad. His goal is to change people’s understanding of the Underground Railroad as being primarily overland.

Similarly, David Cecelski, in his 2002 book, The Waterman’s Song: Slavery and Freedom in Maritime North Carolina notes:

Maritime routes of the Underground Railroad were vital for thousands of fugitives who stowed away, impersonated free black mariners, bought passenger tickets, or enlisted the aid of sympathetic captains and crewmembers. Runaways depended on maritime blacks. …

On 9/10/22, we learned of the massive 1898 history of the Underground Railroad by historian Wilbur Siebert, which now gives us the context for what we learned from the Women History Blog below. Siebert recounts the story of an excursion boat, the White Pigeon. The boat, operated by Austin Bearse in Boston Harbor, would “… run the boat down in the harbor to meet Southern vessels. The practice was to take along a colored woman with fresh fruit, pies, etc. – she easily got on board and when there, usually found out if there was any fugitive on board; then he was sometimes taken away by night”. (Source for this is the womenhistoryblog)

Sources:

“Historian Timothy D. Walker helps tell story of Underground Railroad’s maritime route,” The New Bedford Light. By Joanna McQuillan Weeks, May 2022. Includes interview video of Timothy Walker.

“Maritime Underground Railroad” History of American Women, womenhistoryblog, 2015

William Still, The Underground Rail Road, 1872. Scanned copy, Transcribed copy

“Sailing To Freedom: Maritime Dimensions Of The Underground Railroad.” Webpage of a 2022 exhibit at the New Bedford Whaling Museum.

“Symposium Highlights Enslaved People’s Escape by Water,” by Kip Tabb, CoastalReview.org. May 26, 2022

-

The “Underground Railroad” is often described as following land routes but a great many people, quite possibly more, found they way to freedom by water.

This history is a lesson in Freedom Seekers: The Underground Railroad, Great Lakes, and Science Literacy Activities Middle School and High School Curriculum is a collaborative effort led by Sea Grant educators throughout the Great Lakes watershed.

Abigail Diaz's essay “Great Lakes Vessels Helped Free Enslaved Africans on Underground Railroad” provides a brief overview using the example of HOME, a two-masted schooner, built in 1843 to move grain and lumber in the Great Lakes. In addition to moving cargo the ship, captained by abolitionist Captain James Nugent, secreted many people to freedom.

Author Saladin Allah, the third great-grandson of Josiah Henson, a man who sailed to freedom in Canada is quoted by a reporter for the Canadian Broadcasting Company (CBC) as saying "One of the important things to note about the maritime aspect of the Underground Railroad or freedom ships is that when these ships left the South, our ancestors boarded them as cargo, yet disembarked as passengers — as people," he said. "So symbolically speaking, to berth that freedom ship was also the birth of one's freedom."

Sources:

Freedom Seekers Curriculum website and curriculum.

Abigail Diaz, “Great Lakes vessels helped free slaves on Underground Railroad,” Herald Times Reporter, July 2, 2020

“Great Lakes Region: Pathway For Freedom Seekers, Then And Now,” Here & Now, WBUR radio. By Angelica Morrison, Great Lakes Today October 13, 2017. (audio story)

“HOME (1843),” Wisconsin Shipwrecks.

Bee Quammie, “Freedom Ships and the Little-Known History of Resistance,” CBC, Nov 09, 2020

-

Steamboats facilitated the enslavement of people - estimates suggested that 500,000 to one million enslaved people were shipped via steamship or forced to walk from the Upper South — Virginia, Maryland and Kentucky — to labor on plantations in the Deep South between 1810 and 1865. For some, steamboats were also a means to travel to freedom. This is what is discussed in Steamship Historical Society of America’s curriculum “Mississippi Steamboats: Enslavement and Freedom”

Learn more at: Steamship Historical Society of America’s website

-

The African American community of Weeksville in central Brooklyn was formed in the late 1830's. The occupation of Mr. Weeks, for whom Weeksville is named, may have been a longshoreman (what is known is that was the job of a Weeks who lived there). It was also the home of people who worked as sailors, one of the few jobs open to African-Americans at the time. For example, in the 1840s, Junius Morel moved to Weeksville to be a teacher and principal of Colored School No. 2. Morel was born in slavery, fleeing the Carolinas by ship around 1810, and then working several years as a sailor.

• Great profile with many photos by The National Trust for Historic Preservation “Preservation Magazine” Fall 2022 issue.

• Mullarkey, Lara Steensland. In the hands of their own: The story of the Weeksville School 1840–1893. Teachers College, Columbia University, ProQuest Dissertations Publishing, 2012.

• Weeksville Society web site: http://www.weeksvillesociety.org/

-

During World War II the Brooklyn Navy Yard was the largest naval construction facility in the United States. The demand for war ships and with many men at war, the need for people to fill wartime jobs at the Navy Yard opened up new opportunities for Blacks, other minority groups and women.

Ducat Media, led by Vivian Ducat, produced a series of short films for the New-York Historical Society’s 2012 exhibit, WWII & NYC including one that focuses on the oral history of a Black man who worked in the shipyard: WWII & NYC: Brooklyn Navy Yard at War .

-

Professor Wilbur H. Siebert’s comprehensive history, The Underground Railroad from Slavery to Freedom was published in 1898, after decades of research. A free searchable digital version is available on Gutenberg.org and a searchable scanned copy can be found on HathiTrust.

The William H Siebert Underground Railroad Collection, a compellation oh his original sources is now freely available (there was a fee before) on the Ohio History Connection website.

Seibert research includes many references to the waterways being an important and integral part of the Underground Railroad. Among his very many sources is the work of William Still (1872).

Individuals

African American Maritime Heritage books in our library

These books can be read if you visit PortSide. The library is in the Captain's Cabin aboard our ship MARY A. WHALEN.

If you would like to recommend a book to us, please email chiclet@portsidenewyork.org. We will be thrilled if you buy the book and ship it to us at 190 Pioneer Street, Brooklyn, NY 11231. Thanks!

(Books are in alphabetical order by author’s last name.)

-

PortSide supported Capt. Bill Pinkney’s effort to publish his second children’s book because it is a story for the ages. This book “Sailing Commitment Around The World” is about his voyage as the first black man to sail around the world solo via the southern ocean and Cape Horn. Capt. Pinkney designed that voyage as a vehicle for inspiration and education for children and networked with kids around the world and got the message out before the internet existed to make such things easy. In 1994, he published a book for 1st graders about the voyage, and his new book will bring the story to more young readers. Pinkney’s list of accomplishments is long, on top of that voyage, he was the first captain of the Amistad, was honored by the sailing Hall of Fame, and more. His story offers inspiration for all children; and since representation matters, it is a particularly powerful one for Black children. Please join us in donating and visit his Go Fund Me page. They have a modest goal of $15,000.

The launch of this program was supported, in part, by public funds from the New York City Department of Cultural Affairs, in partnership with the City Council.

Past events:

2019:

Black History Month: We regret that we do not have a venue for public events in the winter. Our “auditorium” is our ship deck, and after September, that’s too cold to use. We ran a digital program by sharing updates on this blogpost. In July, the AMISTAD cancelled their visit to us planned for August 2019 citing issues with crew.

2018:

2nd event: Summer 2018 visits by the historic ship Amistad

Two dates:

Tuesday, 7/24, 10am - 1pm & 2pm - 5pm

Saturday, 8/11, 10am - 1pm & 2pm - 5pm

The replica ship Amistad, built in 2000, is operated by Discovering Amistad. It relates to an important story in American history based on the 1839 episode when Mende captives from Sierra Leone took control of the ship Amistad. The replica Amistad is the flagship ambassador of Connecticut today.

1st event: 1st History Challenge

Wednesday, 5/30/18, 4:00-6:00pm

This event for 5th and 6th grade students from Red Hook schools will occur in the auditorium of Summit Academy. Ten teams from Summit Academy and two teams from BASIS Brooklyn will participate. The public and media are invited. Photo ID required for entry if you are over 18 years old.

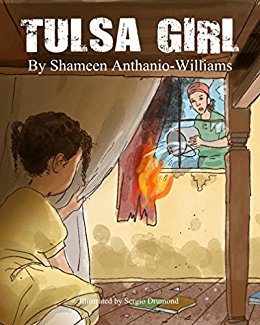

Shameen Ebony Anthanio-Williams

Shameen E. Anthanio-Williams is a commissioned officer in the United States Coast Guard and a children's book author. She grew up in the Bronx and attended the LaGuardia High School of Music & Arts and Performing Arts. Next came the United States Coast Guard Academy and, in 2016, she earned the rank of Commander. Her assignments include Marine Safety & Security, Naval Engineering, and Acquisitions Management. She also holds a master of science degree from George Washington University.

Anthanio-Williams is the author of two children's books: Little Erroll: the story of Admiral Erroll M. Brown, First Black Coast Guard Admiral (2014) and Tulsa Girl (2016). Tulsa Girl is based on the memories of Dr. Olivia J. Hooker - the first African American woman in the US Coast Guard (1945), a doctor of psychology, and a civil rights activist - who as a six-year-old experienced the Tulsa race riot (massacre) of 1921. Anthanio-Williams hopes that people will learn from this history: “Our nation once again finds itself steeped in fierce racial discord, and I want all parents to sit down with their children and teach them what it actually means... I know discussing politics with children is unconventional, but you only have to look at our nation s racial tensions to see what ignorance leads to”

Sources:

Shameen Anthanio-Williams: Facebook, Linked In:

Shameen Anthanio-Williams, webpage for Tulsa Girl:

“Shameen Ebony Anthanio-Williams”, Society of Children's Book Writers and Illustrators

Everybody Wins DC's Facebook post thanking Lieutenant Commander Shameen Anthanio-Williams for sharing her book, Little Erroll: The Story of Admiral Erroll M. Brown.

“Little Erroll The Story of Admiral Erroll Mingo Brown: First Black Coast Guard Admiral,” Indiebound.org