Marine Highway 101 for last mile planning

/This was written by Carolina Salguero, founder and ED of PortSide NewYork, and first posted on 2/19/23. Updated 2/25/23.

What’s this page about?

Concerned about truck traffic resulting from ecommerce warehouses being built near you? Thinking that moving that stuff by water instead of truck could help? Trying to understand how maritime freight works? Confused by maritime jargon? This page is for you.

In communities by the water, the waterways can again be used to move the freight, especially in neighborhoods like ours of Red Hook, Brooklyn, which has a history – and present – of moving freight by water. Expertise is here, and some infrastructure as well; plus, there are experts who can re-install infrastructure that decayed or was removed.

PortSide has advocated for a robust return to using the waterways for freight since we were founded in 2005. See this 2006 testimony and our Advocacy webpage here.

How you can provide input

We created this page to help non-maritime people understand the topic, the terminology, and possible options relating to moving freight by water since our area, Red Hook and Sunset Park Brooklyn are the site of many new last mile facilities on the water or just a block or two away. During the pandemic, a surge of these facilities were built or are being built around NYC, so we hope this resource helps outside our immediate area. A 6/23/22 Red Hook public meeting about last mile is covered here.

We’ve made a blogpost not a webpage so you can add questions and suggestions at the bottom. If you want to comment privately, send email to chiclet@portsidenewyork.org. We’ll incorporate comments (give us time) by updating the text so you don’t have to read a long thread of comments to grapple with this subject. If you’re a maritime person who wants to help with this, we want to hear from you!

We gratefully accept donations here and here as we have no funding for this work at present.

-

After WWII, there was a boom in building highways and a shift to using trucks, once freight was put on ships in containers starting in the late 1960s. This created a unified transportation system where containerships imported huge numbers of containers, and those boxes were put on the back of the 18-wheelers we all know. The development of this system shortened the time to load and unload ships from days to hours, hugely reducing the amount of cargo in sacks and boxes on pallets moved by stevedores and cranes as shown in the movie On The Waterfront.

But some 60 years later, our highways and city streets are choking with truck traffic, and residents are choking on the exhaust of dirty diesel trucks. Highways, bridges and roads are suffering wear and tear from these heavy trucks. Neighborhoods built on fill like ours, Red Hook, Brooklyn, suffer “subsidence” (sinking land) resulting in cracked buildings, potholes, and bigger sinkholes.

The surge in ecommerce intensified the negative effects of this reliance on trucking, and the boom in building “fulfillments centers” (the warehouse your purchase leaves before getting to you) has hit low-income communities of color hard because this is where these places are built. Those communities already suffer health effects from pollution and/or traffic. Last mile warehouses/fulfillment centers create issues of environmental justice (EJ) as described in this 12/9/21 Consumer Reports article in communities that already have a high EJ burden. Yes, these warehouses can bring jobs, but bad jobs do not erase EJ burdens and Amazon’s track record as an employer and union-buster leaves much to be desired.

In communities by the water, the waterways can again be used to move the freight, especially in neighborhoods like ours of Red Hook, Brooklyn, which has a history – and present – of moving freight by water. Expertise is here, and some infrastructure as well; plus, there are experts who can re-install infrastructure that decayed or was removed.

-

Moving freight by water this kind of short distance, waterborne freight within domestic waterways, is called short sea shipping (short because it doesn’t cross a big ocean), or coastal trade, coastal shipping, coasting trade, coastwise trade, blue highway or marine highway. We use “marine highway” since it sounds more like what it is to non-maritime people; and we mention the others in case you want to research this on your own. Jump to our list of Maritime Terminology at right if you want to know vocabulary before the big picture items.

-

Where a boat goes to dock: a dock, wharf and pier are all “landings,” where the boat lands, docks or ties up. Another form of landing that is part of this story are the NYC Ferry landings which are “spud barges,” barges pinned in place by “spuds” the oddball maritime word for when a boat effectively has its own “pilings” (vertical stake of poles holding it in place). That is why the NYC Ferry landings bob up and down sometimes, they are barges.

Some generic boat terms are sometimes used interchangeably: boat, ship, vessel (though technically ships are bigger than boats, speaking informally people will call a ship a boat). There are specific names for boat/ship types that could be involved in this supply chain:

RORO barge (roll on, roll off)carrying trucks, truck trailers, train cars on rails

RORO fast ferries (roll on, roll off), likely using custom-designed rolling carts

Freight ferries such as Harbor Harvest boats

Passenger ferries like NYC Ferry or NY Waterway working at night (with seats removed), though the Coast Guard will need to inspect the boats to determine that the new use is safely viable on the boats, a new COI (Certificate of Inspection).

LOLO barges (load on load off) where freight is lifted on and off by cranes on land

LOLO self-unloading boats that carry their own cranes like this prototype for last mile deliveries.

Containership:

This is how large amounts of freight come from overseas. Containers are stacked on the ship deck. They are usually unloaded by gantry cranes (cranes that straddle the workspace) on land and roll along parallel to the ship on rails like a train track, or the ship can be self-unloading and carry its own cranes. Self-unloading containerships are much smaller and usually export from under-developed countries that don’t have the port infrastructure of big gantry cranes. Ecommerce freight that is manufactured overseas likely comes on containerships, though some express-shipped goods will come in planes.Fast Ferry:

NYC Ferry and NY Waterway boats are examples. They go faster than big, monohull ferries like the Staten Island ferry, by being catamarans riding on top of the water. Currently, fast ferries in this harbor only move passengers, not freight.In the last days of Mayor de Blasio’s administration, he announced a freight vision Delivering Green that proposed using passenger ferries “moonlighting” at night to move freight after the passenger hours ended (midnight to 5am was something we heard.) The ferry seats would have to be removed each night. The freight would likely be RORO not LOLO, but few operational details were presented. The NYC EDC, which runs the NYC Ferry system, has been talking about using those boats and the docks for last mile freight, probably because that ferry system was highly subsidized before the pandemic, and during the pandemic hemorrhaged money.

Tug and barge:

The tug has the engine; the barge, carries the freight. These two can come apart; the tug can leave an unloading barge and go get another one. Barges can be scows (open like buckets; they carry “bulk cargo” loose things such as sand and gravel, no good for ecommerce) and deck barges that have a flat surface you can put containers or vehicles on.

-

RORO = roll on, roll off, the freight is rolled onto the barge with in an 18-wheeler, a smaller sprinter van, little custom-designed trolley for a freight ferry, or something else.

LOLO = “load on, load off” the freight is lifted on or off, not rolled. That means a crane or forklift is used. The crane can be on the land or, if it is on the boat, it is a “self-unloading”

CONRO = container + roll on, roll off. CONRO ships currently call on the Red Hook Container Terminal. A barge could be a CONRO vessel if tractor trailers drive onto it, and the barge also carries containers. Not saying that’s a solution, just that it is physically possible.

Backhaul = the return trip. If the boat goes back empty, that’s a cost. Can freight move on the backhaul?

Bulkhead = maritime term for a vertical wall both on a ship or the wall where land and water meet. Few boats can come up onto a beach, so there has to be either a bulkhead with deep water next to it or a structure protruding into the water (see pier below) for the boats to have enough water to reach the docking location.

Landing = a place where boats can arrive or land. They can take several forms (pier, spud barge, etc.)

Pier = manmade structure on piling sticking out into the water.

Spud barge = spuds are pilings (vertical poles) that pin a vessel (boat/barge) in place. The NYC Ferry landings are spud barges, that’s why they move.

Water depth and vessel draft = you need to have deep enough water for the vessel/boat to arrive at the landing. The “draft” of the vessel is how deep into the water it is, how deep the hull is under water.

Front loading = freight and/or passengers enter the front/bow of the boat. Landings are specially made for front loading ferries with structures that protrude to embrace the docking boat. Due to that, side loading boats (a more common design) can’t dock at those landings.

Side loading = the boat comes alongside (not bow/front in) and passengers and freight get on the boat over its side.

Freight ferry = a ferry specially designed for freight. High speed catamarans of this type will move faster than tugs pulling or pushing barges, making them likely to be more appealing to last mile shippers where speed is key.

Tug and barge freight = tugboats move the barge. Barges can be deck barges (they have a flat top you put the cargo on. This kind would be used for last mile) or scows that have an open bucket shape into which loose stuff such as sand, asphalt, dredge mud are put. These will not be used for last mile.

Harbor ice = one potential limitation of the marine highway is winter ice. Huge chunks can form up the Hudson and float down and be a hazard. Ice can form within NYC harbor in the shallow, slower moving water that is where many local last mile facilities are located on the waterfront. When there is significant harbor ice, trucks have an advantage.

TRUs = diesel refrigeration units

eTRUs = hybrid electric refrigeration units

-

Guide to Amazon ecommerce warehouse terminology here describes kinds of places:

• Fulfillment centers (FCs),

• Sortation centers (SCs),

• Delivery stations (DSs),

• receive centers,

• sub same day,

• specialty

fulfillment center vs warehouse. Every fulfillment center is a warehouse, but a warehouse is not a fulfillment center.

B2B business to business

B2C business to consumer

3PL 3rd party logistics provider – they usually run a fulfillment center (as opposed to a warehouse). This means that a local ecommerce site can have management layers: property owner, company that built the warehouse, 3PL, the shipping company such as Amazon. This is important when you think of trying to influence size, siting or activity of these fulfillment centers, because who do you talk to?

-

Truck traffic which means pollution that damages local health, is dangerous, noisy, causes road subsidence (sinking) which is a big concern in Red Hook that is built on 19th century spongy landfill; and clogs the road so much that all other users are impacted. All of this deteriorates the quality of life.

High carbon footprint a concern for the planet as a whole.

Environmental Justice (EJ) The fulfillment centers tend to be sited in low-income communities of color that already have environmental justice (EJ) issues, so the ecommerce fulfillment centers represent yet another EJ burden. They represent a convenience for the shopper outside of the neighborhood at the cost of the neighborhood with the fulfillment center. See this 12/9/21 Consumer Reports article by Kaveh Waddell that studied this nationwide. Andrea Sansom of Red Hook reached out to Kaveh Waddell, and he is now looking into the Red Hook last mile situation. PortSide was part of a tour given by local advocates to his research team on 3/4/22.

Quality of the jobs. On this, there can be quite a range with UPS being unionized and touting their history of employees rising up the ranks from low-level to CEO, and Amazon which is known known for fighting unions, firing whistleblowers, high employee burnout and more. Jobs are sometimes presented as a compensation to the neighborhood for the EJ burdens above; but communities should not have to face more burdens in exchange for jobs; bad jobs do not erase EJ burdens. On 4/1/22, in a David beats Goliath story, the start-up Amazon Labor Union was able to unionize a Staten Island Amazon warehouse, the first one in the USA.

Damage to local retail. This has been less discussed in the urgent focus on trucks; but ecommerce destroys local retail, and local small businesses provide an array of secondary benefits to a community. As a jump-off for your research, look for examples in articles on how local small businesses were damaged by the rise of malls and big box stores. The ecommerce paradigm is the latest phase in a long process ravaging local retail, the businesses that are often mainstays in a community that offer benefits beyond what they sell.

-

Since at present, there is no mandate to make last mile shippers use the marine highway, we think it is key to determine if the marine highway is cheaper, faster or both than trucking. Note there is trucking INTO the last mile facility and OUT of it.

Key questions are: where and how has the freight arrived in the region? Has it arrived in a marine port (via international ship)? Has it been sent to this region by truck or train to go to an intermediate warehouse (middle mile) before going to the last mile warehouse? Is it coming straight from the airport? If so, do they have a dock (a marine terminal) there? Note that all the region’s airports ARE on the water (JFK, LAG) or near water (Newark). All that determines:

1. Where the freight would get on the water

2. How the freight is packed at that point in the supply chain (air container, on pallets, in loose boxes)

3. That determines what can pick it up (forklift, bigger crane)

4. Then, where does it get off the water?

• First, huge volumes of it go to the fulfillment center for sorting. Is that on or near the water? Is it water deep enough to use for shipping? Permits to dredge (make the water deeper) can be hard to get for environmental reasons.

• Next, when it goes to the consumer, if it moves by water, could it arrive in parks, at street ends, along public-access esplanades? Or does this have to happen in a designated maritime industrial location? Answering that becomes a land use issue, not just a transportation logistics issue. At PortSide, we think NYC is overdue to change zoning conventions that say maritime activity cannot happen near “public access waterfronts” e.g., parks and vice versa. Changing this is one of the core principles in our maritime advocacy work.

We think multiple marine highway solutions could operate at the same time in this harbor, and that the marine highway should move more than just the last mile freight.

Once a hyperlocal marine highway is in place, more industry sectors can use it. As with many things, the start-up period represents the big hurdle.

-

At this point of the pandemic, supply chain = mashugana which is Yiddish for a crazy mess.

The supply chain looks like this: Manufacturer (usually overseas by now) puts goods on a plane or ship that arrives at an airport or marine terminal and gets unloaded onto a truck.

It then goes to a middle mile warehouse where containers are opened and stuff resorted until it is sent out on a truck or (we hope) marine highway to a last mile fulfillment center (like those being built in our neighborhood) and then a small truck, Sprinter van, car or cargo bike takes it to the consumer. More detail below., and see the first illustration in the collection below all the text on this page.

-

At present, there is a lack of tools to mandate or encourage marine highway use, though a bill has been introduced in the City Council to mandate that in SMIA (Significant Maritime Industrial Areas) 80% of the freight has to move by water, so until that or some other mandate or incentive is found, it seems that the maritime option needs appeal to ecommerce shippers (eg Amazon, UPS, FedEx) in terms of cost, speed, reliability or some combination of those three.

If you know places that have tools to mandate or encourage maritime uses or if you can think of ways to accomplish this, please comment below or email us. The federal Maritime Administration (MARAD) told us about the following Virginia tax incentive.

At present, NYC government policy at DOT and City Planning contends that the fulfillment centers are “as of right” (a zoning term that means no special permit is needed), and thus they can be built without responding to any community concerns or needs. Result? Lots of these places with no oversight, no strategy to keep communities from being overrun by their trucks. Some places, such as our neighborhood of Red Hook, may even now have too many ecommerce fulfillment centers being built for them to be viable. There may be too much gridlock for them to move.

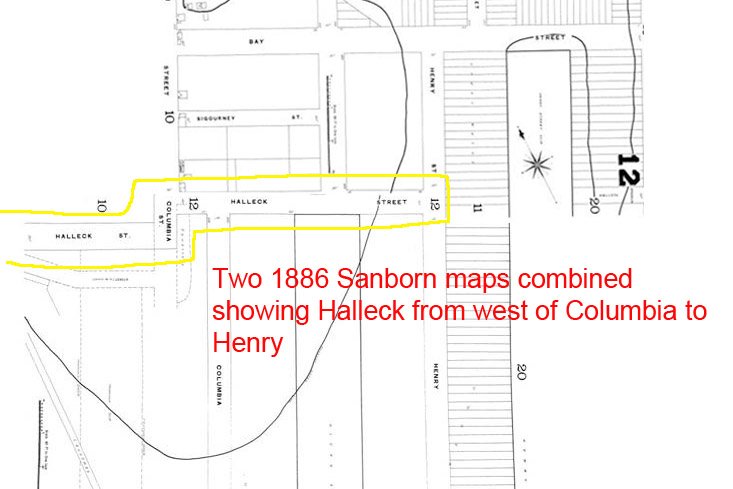

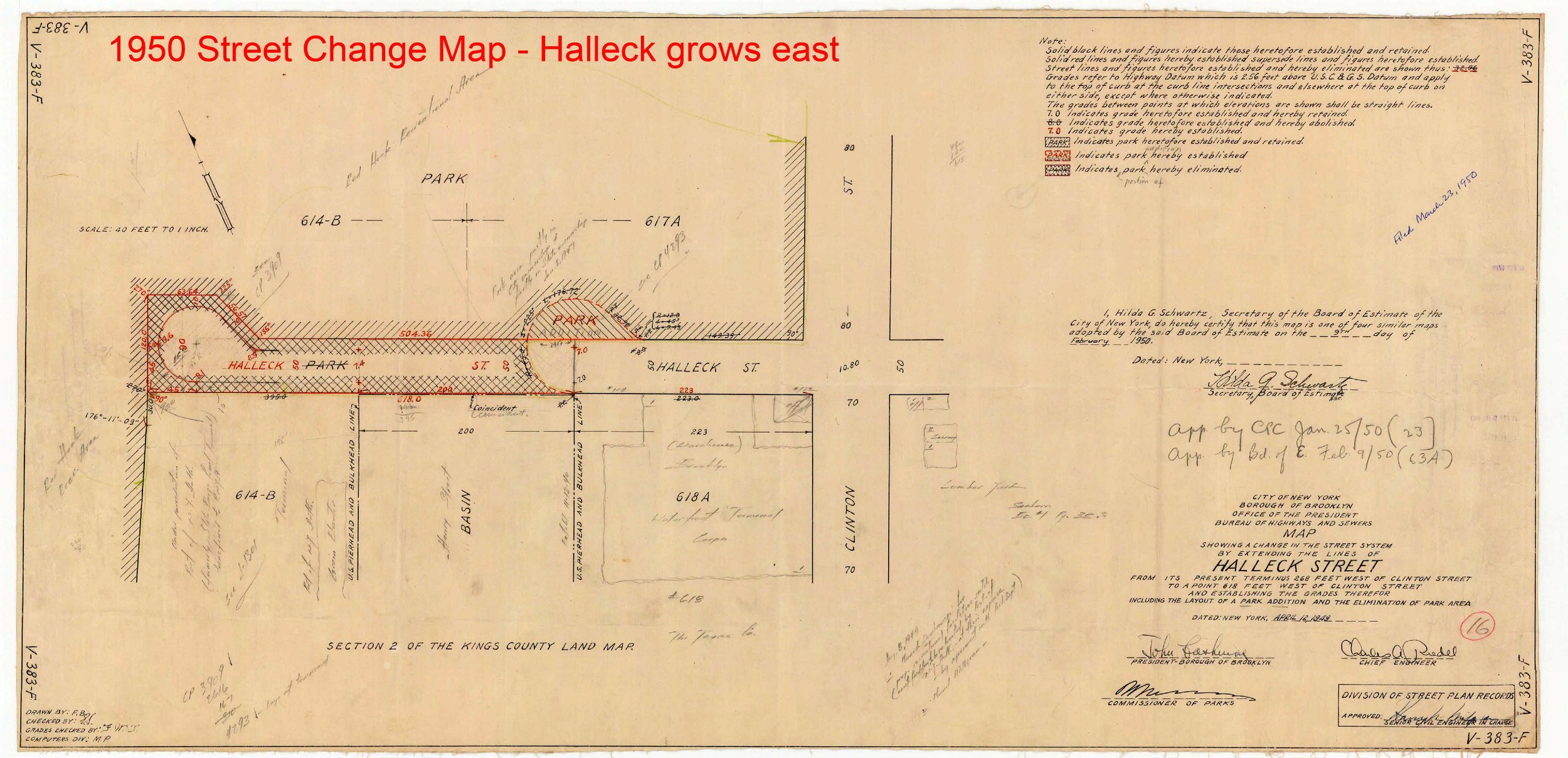

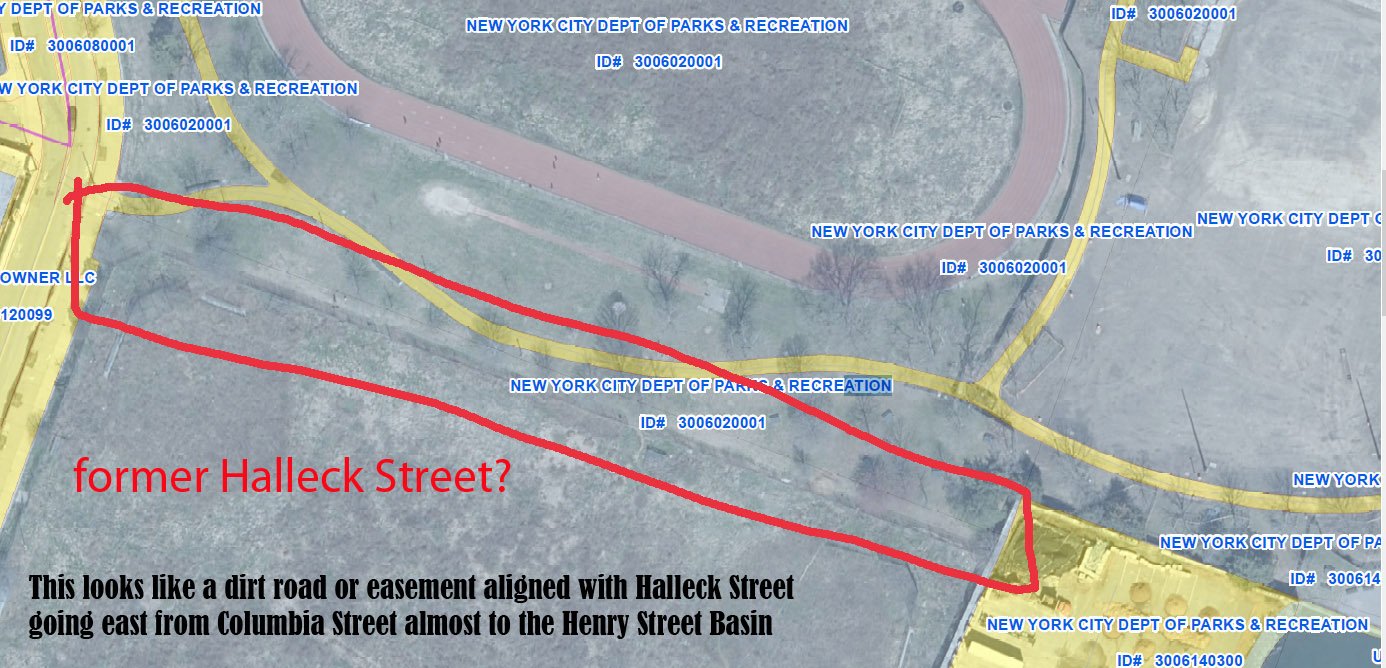

The slide show below relates to the proposed new truck route along Halleck Street in Red Hook, discussed in the section below these images called “Solutions - possible and proposed.” It appears that Halleck grew and shrank in cycles over time. We are not sure we have captured all its phases. Not all the “shrinkings” seeem to have been done via an official NYC process; part of Halleck Street that looks like park is still “mapped” as a street. A long email thread with community members and staff of elected officials contributed to this plan and to finding some of these images. Big thanks to our advisor Eymund Diegal and our Historian/Curator Peter Rothenberg for researching this history too.

-

Raise bridge and tunnel tolls on trucks (routes controlled by the Port Authority of NY & NJ) to encourage moving the freight onto the water.

Look to how Europe and Asia use marine highway for short hauls. The USA lags far behind and NY harbor even more so.

On 4/18/22 NYS Assembly member Marcela Mitaynes (D-Brooklyn) introduced in the 2023-24 legislative season Bill A1718 which “Establishes an indirect source review for certain warehouse operations; requires the department of environmental conservation [NYS DEC] to conduct a study regarding zero emissions zones. This is an update on her earlier bill A9799 covered in this article.

New bills have been sponsored in the City Council Members Jennifer Gutiérrez (D-Williamsburg), Sandy Nurse (D-Bushwick), Selvena Brooks-Powers (D-Far Rockaway), Julie Won (D-Astoria, Shahana Hanif (D-Gowanus/Park Slope); and Lincoln Restler (D-Downtown Brooklyn), Public Advocate Jumaane Williams, and Brooklyn Borough President Antonio Reynoso.:

• Intro 923, “This bill would require the [NYC DOT] to conduct a study on the impact of last mile facilities on the street infrastructure and communities they are situated in, including estimating the amount of delivery vehicles arriving at or departing from each facility, and the impact that additional vehicle traffic has on parking, street congestion, vehicle collisions and other traffic incidents.”

• Intro 924, “requiring the [NYC DOT] to study street design as a means to limit or reduce the use by commercial vehicles of streets in residential neighborhoods.”

• Resolution 501, “Resolution calling on top maritime importers to New York City ports to commit to making the City's streets greener by reducing truck traffic and using marine vessels for last mile deliveries throughout the boroughs.”

Copying the following bill descriptions from an EarthJustice.org update:

Int 707 – A Local Law to amend the administrative code of the city of New York, in relation to air quality monitoring at designated “heavy use” thoroughfares

Int 708 – A Local Law to amend the administrative code of the city of New York, in relation to redesigning the truck route network to improve safety and reduce traffic congestion and emissions

Int 721 – This bill would require the New York City Department of Transportation to include in its truck route compliance study information about the feasibility of developing a web-based interactive mapping application that integrates the City’s truck route map with global positioning system technology.

Int 898 – A Local Law to amend the administrative code of the city of New York, in relation to translating the citizen’s air complaint program portal into the designated citywide languages

Last-mile zoning text amendment – The special permit would set forth the following conditions:

o Any last-mile warehouse must be at least 1,000 feet from any school, park, nursing home, or public housing development.

o Last-mile warehouses must be at least 1,000 feet from another such facility.

o Last-mile warehouses located in what’s called a Significant Maritime Industrial Area, which are designated waterfront areas, must conduct 80 percent of deliveries by marine transportation (see map).

Halleck Street - changing a Red Hook truck route:

A solution that does not reduce the trucking in Red Hook but would make one route safer is to re-connect Halleck Street along the southeast side of Red Hook, make it a fenced off truck route, and move the truck route there from Bay Street. The Bay Street truck route goes through blocks of very popular parks with ball fields, a swimming pool, BBQ areas, the Red Hook Food Vendors, and BASIS school. The Parks Department has pushed back saying “park land is sacred.” We think children’s lives are sacred, and we would rather lose access to a small patch of lightly-used park land than have kids - or adults - lose their lives or limbs. The term for taking over park land this way is “alienating park land,” and it is done at the state level, called “Alienating Park Land. See the NYS SHPO Handbook on Alienating Parkland.

According to NYC Street Map, Halleck is still mapped (officially exists as a street) except for between Henry and Columbia. Bay Street is parallel and above Halleck on the map. At some point in the early 2000s, the short section of east-west street next to the Todd Memorial Triangle (the triangle towards the left of the ellipse above) was made impassible by vehicles by the insertion of raised sidewalks on the split part of Columbia Street on either side of the triangle; however, it is still mapped as a street! In the early years of the Bloomberg administration, CB6 tried to get Halleck Street made a truck route, and Parks pushed back. The former CB6 District Manager says that Parks made site changes to prevent Halleck re-connectable. Is this when those sidewalks were added?

Got any ideas for other solutions?

-

Boat permits. Boats, like buildings, have to be inspected and approved for certain uses. If passenger ferries are to moonlight moving freight, the US Coast Guard (USCG) has to inspect the boat for a stability test and other concerns to make sure it is safe for cargo. The USCG will also mandate the number of crew needed for freight use. Trucks only need one driver, all the boats under discussion (unless autonomous vessels are really developed) will need more personnel, called crew, than the trucks and vans. We hear that the USCG has already been asked to look at the NYC Ferry boats for freight use.

Construction permits are needed to build anything in, on, or over the water. In addition to addressing concerns about the structures’ strength, other factors are assessed. There are City building permits. There are permits from the NYS Department of Environmental Conservation (DEC) looking to protect the environment. These have been THE bottleneck for maritime construction since around the 1980s, and crushed Red Hook’s ability to build back maritime infrastructure we used to have. See 2005 PortSide testimony about this here.

DEC rules could make it hard to install a marine highway in that the permit applications could be outright rejected; or, as we heard from a Red Hook landowner in 2018, the DEC would now allow him to rebuild a pier long-gone from his property, but he would have to pay 40% of the cost of the pier into an environmental remediation fund, increasing his costs by 40%. DEC policy is hindering the revival of marine highway uses, the greenest way to move freight, by focusing on the environmental criteria in their framework.

Permits are also needed from the federal US Army Corps of Engineers (USACE). The USACE permits regulate “discharges of dredged or fill material into waters of the United States and structures or work in navigable waters.” Navigable means usable by boats. Think of those as public water spaces protected as usable corridors through the waterways that the federal government maintains by dredging. They want to make sure that nothing put there restricts navigation, e.g., use by boats.

Yucky fun fact: before there was a sanitation department, New Yorkers dumped their garbage at the waterfront, using garbage as landfill. (See this fascinating book). In the late 1800s, the feds got so concerned about “encroachment” from NY and NJ sides and that the Hudson River would get too narrow to be usable for shipping that they instituted pierhead limits (a limit on how far out into the water a pier could go). These limits continue to this day.

All waterways are not public space. There is privately owned property underwater reflecting where piers stick out into the water or used to. Since Red Hook used to have a lot of piers, there is a lot of privately-owned land under water. See here. This needs to be considered when planning where boats can go.

-

NYC zoning has meant that maritime freight uses have been termed industrial and assumed only to go in an M zone (manufacturing zone). The new big waterfront parks such as Hudson River Park and Brooklyn Bridge Park are no longer M zones (that was changed to make them parks), so introducing freight there maybe requires zoning changes and certainly requires waterfront park managers and users to accept that, for the greater good of all, some kinds of freight use is OK in a park, that parks can be multi-use (as in zoning concepts) places. Hudson River Park even prohibits vehicle deliveries to historic ships on their piers so how to get freight off boats that come into that park if the park won’t flex on that?

Current zoning, even in M zones, does not protect or incentivize maritime freight use; the regs just say it is allowed. Relevant zoning terms beyond M zone are:

IBZ = Industrial Business Zone

SMIA = Significant Maritime Industrial Area

OZ = Opportunity Zones. A federal program created during the Obama administration created OZ (opportunity zones) to encourage investment in economically distressed areas such as Red Hook; and that probably supported investment firms developing so many last mile facilities here, but the terms of the OZ program do not affirm maritime use in any way. We need to find ways to incentivize maritime use!

-

There used to be lots of barges moving freight across the harbor. Can’t we just do the same thing now?

Times have changed! There was once maritime infrastructure for docking freight boats all over the city, piers for big ships, for smaller ships, for tugs and barges, and rail float terminals where barges loaded with railroad freight cars docked and the train cars could roll right off onto the tracks. This TrainWeb page shows how much freight rail there was in South Brooklyn alone. The overwhelming majority of all that infrastructure has been removed. Working waterfront areas were rezoned from M (manufacturing/industrial) to R (residential), C (commercial like IKEA) and parks.

Waterfront parks have been installed in a lot of central NYC where the highest density of ecommerce will occur, and the planners of those parks have been deaf for two plus decades to suggestions from PortSide and others to keep maritime options within the parks (search for the word “parks” in here.) Fences ring the waterfront in these places, and fences get in the way of boats docking and cargo movement from vessel to pier. Piers have been built for pedestrians, not for boats. Permitting for waterfront infrastructure is harder than back in the day when there were piers used by working waterfront all over NYC.

Yes, NY Harbor still has a lot of working waterfront and is, since the pandemic, the largest port in the USA (in terms of international cargo received), but that infrastructure is concentrated in a few places, not all over the place in a way that would support delivering ecommerce freight. Building a marine highway to move things within NYC means we have to start almost from scratch.

Some maritime infrastructure has recently been added in NYC, those are the docks for the NYC Ferry system. In the last days of Mayor de Blasio’s administration, he announced a freight vision Delivering Green that proposed using passenger ferries “moonlighting” at night to move freight after the passenger hours ended (midnight to 5am was times slot we heard.) The NYC EDC, which plans and oversees the NYC Ferry system, has been talking about using those boats and the docks for last mile freight, maybe because that ferry system was highly subsidized before the pandemic and hemorrhaged money during the pandemic. Using that system for freight could justify keeping the service while helping reduce the ecommerce truckopalypse. October 28, 2022, The NYC EDC got $5.16MM grant from the federal Maritime Administration (MARAD) to “to upgrade and improve six harbor landings” to have them serve as new locations for last mile freight: Stuyvesant Cove (Manhattan), Downtown Manhattan Heliport (Manhattan), Pier 36 (Manhattan), Oak Point (Bronx), 29th Street Pier (Brooklyn), and 23rd Street Pier (Manhattan) and “the upgrades include installing floating platforms with appropriate tie-up and vessel docking hardware to successfully secure vessels and allow for unloading via crane, hand truck, e-bikes, or motorized vehicles.” PortSide’s advocacy is mentioned in the quote in the press release from Congresswoman Nydia Velazquez.

Speed. How is next day delivery possible if gridlock means the BQE alone can take hours!

Your toothbrush is not flying from China to Park Slope on next day prime service!

Sellers such as Amazon use algorithms to track spending patterns to pre-order what they see consumers tend to order, so that the predicted stuff is in the middle mile warehouse or fulfillment center by the time you order it.

What do mode and intermodal mean?

Mode = the means of moving the stuff (truck, rail, ship, air).

Intermodal = more than one mode is involved, e.g., an intermodal terminal could receive by rail and send out by barge, or come in by plane and leave by ferry.

Freight is packed in different ways for each mode, and the packing system of each mode needs to be considered when changing modes to determine what kind of equipment is needed to make the shift.

For example, a 40’ container on a ship is bigger than an air container in a plane so the same machinery is not used to move them, and UPS trucks hold stacks of boxes.

Note that shippers want to avoid changing modes as much as possible as each mode change takes time and labor which adds cost.

Isn’t it the Port Authority’s job to fix this?

Not really or only in part. Their seaport focus is the international move and up to the first stop after the port, a truck depot or warehouse, not the whole supply chain to you.

However, since a lot of ecommerce freight comes in by air (mainly JFK and Newark) and truck, this does affect the airports, bridges, tunnels run by the Port Authority, they are studying the ecommerce onslaught too; and they are making other sorts of deals relating to all this. They announced a Newark Amazon Air Hub. This then faced community push back. Newark airport is also where a lot of UPS freight arrives and, just across the I95 highway from Newark airport, UPS is opening an 880,000-Square-Foot, 150 acre distribution center at MOTBY in Bayonne. If the Port Authority raised tolls on trucks coming into NYC that could incentive shippers to get freight off trucks and onto the water.

If ecommerce goods are arriving in Port Authority marine ports (Newark and Elizabeth in New Jersey, Global Container Terminal (formerly called Howland Hook) on Staten Island, and Red Hook, Brooklyn), it is our understanding that the freight first goes to a regional middle mile warehouse (often inland in the Lehigh Valley of eastern Pennsylvania) before being repacked into shipments coming back this direction to the local, last mile fulfillment centers like the ones being built in Red Hook.

That means that a container arriving in any of the Port Authority marine ports will NOT come straight to the waterside Red Hook or Sunset Park fulfillment center by boat. Bummer! However, how all this stuff moves is the local part of the supply chain we are trying to better understand.

Cautionary tale: the Port Authority was founded 100 years ago to build a cross harbor freight tunnel which has yet to happen. Plans are in the works to do that, and it would reduce trucks coming over the bridges and tunnels to fulfillment centers.

This page is dedicated to John Tylawsky who was one of PortSide’s advisors on the last mile marine highway topic. He jumped right in to help and appeared on pandemic zoom calls and email threads and advised us directly. He was an all-around great guy, a SUNY Maritime grad, a marine engineer, and Principal of Altair Transportation founded to do last-mile marine highway work. He crossed the bar unexpectedly on January 12, 2022. Think of him whenever you see the Buchanan tug MISTER T go by, that boat was named after him.