I check the weather websites. This looks like hurricane Irene plus some.

We convene a crew meeting and start hurricane preparations. School docents become a Sandy prep squad. By end of day, the deck was cleared of anything that could blow, and I am calling and emailing around for crew to help prepare and to ride out the storm on the ship.

Friday morning, after more info about the storm, I am trying to find a protected berth for the tanker MARY A. WHALEN. Just days before, we received word that our application had been accepted; the ship was on the National Register of Historic Places! Since the MARY is not fully restored, she lacks some equipment that would help her in a big storm: a working engine (eg, the ability to run away), machinery to raise her anchors if dropped to hold us in place, and a winch to haul in docklines under load. Compensating for that involves some extra forethought.

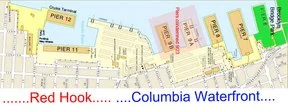

Despite our efforts, we can’t find a good alternate berth for the MARY outside of the Red Hook Container Terminal. Hughes Marine says “We’re out of space. You’ll be able to walk across Erie Basin by the time this is over; it will be so full of vessels.” A contact at a shipyard says “we flooded during Irene, and this one looks to be worse, you sure you want to be over here?” “No and good luck,” is my answer.

After more checking of the weather, I decide to move the MARY where she rode out Irene, on the other side, the north side, of our current Pier 9B. (The south side lines up with the end of Degraw Street). For non-sailors, here’s how this kind of calculation goes:

Winds were expected to start from NE, swing around to the East and end up SW, but this could always change. If rough weather were coming from anything west to southwest, our current position has us exposed to the wind from the southwest and the fetch (long stretch of water over which wind can build up waves) from Staten Island up the Buttermilk Channel.

The fendering (the wooden cribbing protecting ship and pier) is not robust on this side. A big advantage to the north side are some pilings at the inshore end that stand much taller than the pier and which would help prevent the tanker from riding up onto the pier if the surge were really high.

The north side would have us more exposed from winds at the start of the storm, but the hill of Brooklyn Heights and the pier to the north of us (even though it has no shed) would provide a compensating wind break.

As the wind clocked around to the south, a wall of containers near the bulkhead would provide a windbreak to the east, and the pier shed would be an enormous windbreak once the wind went south of east.

A final consideration was that in the extreme case of docklines failing while we were on the northside, the tanker had a chance of bouncing around inside the space between the two piers for a while, maybe long enough for us to get other lines out or call for help; whereas, on the southside of the pier, if our docklines broke, tide or wind could shove the ship up on the rocks nearby to the south (surely the death of the tanker) or shoot us down the Buttermilk Channel towards unknown risks.

I began calling tugboat companies to request a tow. Everyone is busy with storm prep so getting a tug takes a while. I have the tug turn the MARY around so her stern faces east, putting her heavier end towards the expected wind direction. Her light bow is my worry.

The tug’s crew helps us put out storm lines, more lines than we would normally use, and double and triple parted lines. (Instead of a line just going from boat to dock, a triple-parted line goes from dock to boat to dock to boat). The lines are set with a lot of slack to allow the boat to rise during the expected surge. During Sandy, Peter Rothenberg and I will go out in the wind and rain to ease the lines as necessary

From Thursday until Monday, a changing array of volunteers bang through a punch list: gangway lashed to the deck. Gas generator moved near entry hatch and tested. Gasoline, food, and water bought. Weepy portholes caulked. PortaSan moved inside the pier shed so it can't blow away.

More calls to look for crew... Commercial boats have paid crew, but most historic vessels rely on a corps of volunteers and; with so many boats to protect, available bodies were scarce. Compounding that, due to the danger, some spouses do not allow their partners to volunteer on the historic ships during the storm. Danger is one thing for paid crew; as a volunteer, it's another.

I ask Peter Rothenberg, our volunteer museum curator, if he wants to be crew. Peter makes a speedy calculation, “I hesitated for a moment, thinking this may be really unwise, and then said yes, probably being more reckless (brave?) than normally, because I had just lost my mother, and thus she was unable to question my judgment.”